Features

New Athenians

The Institute of Classical Architecture & Classical America (ICAA) recently announced an important reprint of James Stuart and Nicholas Revett’s The Antiquities of Athens, originally published in three volumes, the first in 1762. Hopefully, the Princeton Architectural Press re-issue will influence current Classical architects and patrons to reanimate the elements, ideas and nuances of Athenian architecture as the original books did in their day.

During the early-19th century, British and American architects studied the proportional ratios and refined details from Stuart and Revett’s magnificent engravings. They created a new expression called the Grecian style by combining these elements in compositions devised by Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). The Anglophones used the Greek architectural language for rhetorical as well as formal purposes. Opposed to the imperialistic ambitions of Napoleon, whose architects synthesized the heritage of Roman emperors and renaissance princes, the English speakers sought to embody the democratic associations of Athenian buildings during the age of Pericles and the 4th century B.C.

English architects began to build Grecian structures after Napoleon crowned himself emperor in 1803. The tastemaker Thomas Hope was not an architect himself, but he spurred the movement by engineering the commission of Downing College at Cambridge as a Grecian set of buildings in 1806. In 1807, he published a folio about his house, and his collection of Greek vases and furniture in London—Household Furniture and Interior Decoration. A major exhibition on Thomas Hope will open at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London this March and come to the Bard Center in New York this summer. It will show how Hope developed and pushed the archeological style and influenced many designers.

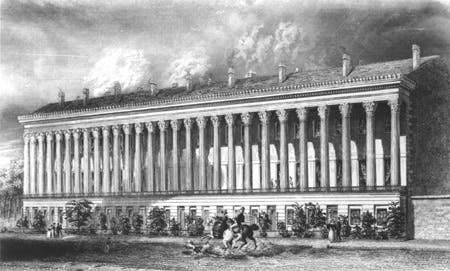

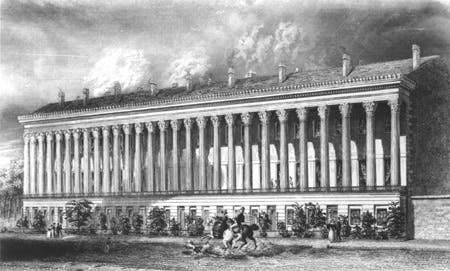

The Grecian style dominated taste in architecture and interior decoration around the English-speaking world of 1812. During the 1820s and early 1830s, American-born architects relied upon Stuart and Revett to build substantial structures: William Strickland in Philadelphia; Isaiah Rogers in Boston; and Alexander Jackson Davis, with his mentor, Ithiel Town, in New York. American cabinetmakers like Isaac Voss, Anthony Quervelle and Duncan Phyfe responded by making architectonic Grecian furniture that was compatible with both institutional and residential buildings. Although The Antiquities of Athens was 70 years old in 1832, it and subsequent publications were vital when Strickland incorporated its information for the Exchange in Philadelphia and Rogers and Town and Davis were locked in competition over designs for John Jacob Astor’s Park Hotel in New York.

We know that Alexander Jackson Davis had access to the original volumes of Antiquities in Town’s magnificent private library. Strickland and Rogers probably did too at their respective athenaeums. By the early 1830s however, copies of Stuart and Revett’s images were ubiquitous in British and American architectural books. The Doric, Ionic and Corinthian paradigm illustrations in Minard Lafever’s The Modern Builder’s Guide of 1833 are notable examples.

Canonical Models

Stuart and Revett presented restitutions of the ancient Athenian buildings they studied for five years in the 1750s. They also extracted columns and entablatures as corner conditions just as Palladio had done to demonstrate canonical models. Like the renaissance master, Stuart and Revett show the image, nuance of details and the proportional symmetria independent from the specific building. This allowed architects to employ the types in new configurations. In the U.S., the Grecian examples virtually superseded what we think of as Roman models from 1830 until the Civil War.

Specific Grecian styles developed in Philadelphia, Boston and New York reflect the work of dominant individuals like Strickland, Rogers and Davis. In New York, this was achieved through a concentrated collaboration between aspiring architects from 1830 to 1835. Similar metropolitan schools also developed around the most active cabinetmakers. Through books published in Boston by Asher Benjamin and in New York by Lafever, metropolitan styles also guided builders who moved west and south. It was the New York Style, however, that had the most influence within its urban context and spread most widely throughout the country.

The New York Style was crystallized in a monumental series of residences called La Grange Terrace, which spawned development in other residential and institutional buildings. In addition, specific details published in The Modern Builder’s Guide and subsequently in The Beauties of Modern Architecture by Minard Lafever, were carried to new states and territories by emigrating builders. They imitated patterns and details from the books but also ordered ready-made New York Style ornaments supplied by manufacturers along the Hudson. Finally, with increasing financial pressures resulting from the economic depression, which began in 1837, several architects who helped initiate the style moved elsewhere: Charles F. Reichardt to Charleston, SC, and James Harrison Dakin to Mobile, AL, and New Orleans, LA. Able to stay in New York, Alexander Jackson Davis and Minard Lafever built in town and country and shipped Grecian designs to clients in upstate New York and Ohio.

A New Expression

Four of the nine La Grange Terrace houses on Lafayette Street in New York City remain. The terrace has attracted architects who have studied and documented it for over 100 years. They have done this to understand American culture of the 1830s and grasp its vitality. In doing so, they have also recorded successive stripping and demise. 175 years ago, citizens flocked to see the structures out of curiosity. They were awed by the reanimation in New York of Hellenistic and Palladian architectural elements in a new neighborhood of unexpected richness. Like several other rows in what was still a surprisingly remote location between Houston and 14th streets, La Grange Terrace was a chain of private dwellings that looked like a Palladian palace.

The city had begun to change with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1824. “Clinton’s Ditch” brought prosperity, power and a new cultural ambition to New York. The Marquis de Lafayette visited the U.S. from August 1824 to September 1825 and his itinerary began in New York. Within a decade, fevered development north of Houston Street created a triangle of outstanding residential, institutional and commercial structures. A broad base ran along Bleecker Street and tapered to a heart around Washington Square. Branches east and west from the dual spines of Fifth Avenue and Broadway decreased in width toward the union of many avenues at 14th Street. Washington Square had an open, London-like ambience. On the other hand, the Astors opened an insulated street for themselves, Lafayette Place, and La Grange Terrace was erected by the family’s contractor, Seth Geer. The denominations of the buildings and the street were inspired by the Marquis’ visit. La Grange honors Mme. de Lafayette’s ancestral estate near Paris and her husband’s surname is, of course, also that street. The young “architectural compositor,” Alexander Jackson Davis claimed that the building was “so named by me.”

La Grange Terrace was curiously attractive because it was made of marble, not brick. The famous row of red brick houses on Washington Square North is much less remarkable. Its format is a variation on a Georgian type from London. In New York, it was in the familiar 15- to 32-ft. widths all along Broadway and down adjacent streets. The doors of the earlier versions had a delicate detail that Alexander Jackson Davis jeeringly called “frippery.” The patrician versions on Washington Square still had doors poised atop a high stoop, but around them, heavy Doric and Ionic columns in marble provided gravitas.

La Grange Terrace was located on the more sequestered Lafayette Place. Points of entry to each house were not elevated upon a stoop but brought close to street level. Columns and entablatures emphasized each door, but they were part of a larger idea that created a unified socle across all nine buildings. Although each entry was marked by gas lights flaring from Roman candelabra, the emphasis was certainly not on each family’s castle. The continuous base level supported 28 Corinthian columns to create the most distinct aspect of what was also called Colonnade Row. Drawing rooms from the principal story opened onto the “superb Grecian Corinthian Terrace,” and one could look down upon it from the windows in the principal bedroom on the third story. No dormers punctuated the skyline above the entablature. Instead, an archaeological rhythm of palmettes capped the corona. For those who could not enter, a full newspaper description of interior features was published in April 1833 by auctioneers James Bleecker and Sons, who would start the sale of the first house at $22,500, which would be “positively sold to the highest bidder.”

La Grange

The entry of each house is defined by a pair of fluted Doric columns that support a variation on the Choregic Monument of Thrasyllus entablature published in the second volume of The Antiquities of Athens. A continuous run of guttae repeat beneath the taenia, and laurel wreaths embellish the frieze. The columns stand in front of wooden piers that frame the paneled door.

The La Grange façades were set back from Lafayette Place by “handsome courts” edged with cast-iron railings. A wide gate accessed the stoop that rose gently to the portal. Cast-iron candelabras rested upon marble pedestals at the edges of a deep slab of marble to give broad access to the threshold and portal. Stout balusters of unusual conical form sharply contrasted with the pedestals. The combination of ordinary and extraordinary elements at La Grange is characteristic of its design.

A more discrete gate to the north accessed steep steps by which deliveries were made to the kitchen level. The stairs approaching the La Grange entries were lower and more gradual than the typical stoop. Each consisted of two or three risers from the sidewalk to a short path of diagonally placed marble tiles. Two marble steps were contained between the pedestals approaching the deep marble platform. One finally stepped upon the euthynteria. This deep threshold led to the entrance hall with a “diamond marble floor” and dining and sitting rooms.

La Grange Terrace had nine entries set between 28 engaged piers of one-by-three-ft. marble blocks. Windows were set within two adjacent piers followed by the next unit’s portal. The piers supported a plain architrave with a simple cornice. Called the “Egyptian Order of Architecture” by Theodore Sedgwick Fay in Views of New York, the arrangement actually imitates an elegant type of 18th-century French rustication used by Joseph Mangin and John McComb at the New York City Hall (1802-1812). Martin Euclid Thompson employed this treatment in 1824 on the ground floor of the Branch Bank of the United States on Wall Street, now in the Engelhard Court of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The typical New York house had a portal with an arch emphasized by emphatic voussoirs. The door surrounds had a “frippery” of wood carving and the ensemble was set atop a high stoop with a steep flight of stairs from pavement to landing. At La Grange Terrace however, the entry was subsumed within the socle. Although it was defined by elegant trabeation with Athenian references, compared to the typical arches, it was integrated within a larger system. Although the socle is by now denuded, it remains identifiable as a continuous support for the range of 28-ft.-tall solid-marble Corinthian columns. These also follow an Athenian prototype – the Choregic Monument of Lysicrates. The Corinthian capital is inherently susceptible to invention and this model is particularly crisp and refined.

The Choregic Monument of Lysicrates, built in 344 B.C., was a celebratory base for a bronze tripod. It still stands in Athens and may be the first exterior use of Corinthian architecture. Like the copy at La Grange Terrace, the column shaft rests on an attic base and a square pedestal. Twenty-four flutes terminate in leaf-like protrusions instead of having an astragal below the capital. The base of the capital is encircled by 16 tongue-shaped leaves, surmounted by the usual eight sharply cut acanthus leaves. Each pair is pinned together by a flower. Above the leaves, the stalks and volutes ebulliently spring to support the dramatically projecting horns of the abacus. Other helixes oppose each other on center with a palmette balanced upon their vortex. By comparison to the exquisite and precise carving at Lysicrates, the La Grange capitals are crudely carved and stocky. As at Lysicrates, the columns supported an Ionic entablature with a corona crowned by elegant antefixes in the shape of palmettes. The northernmost house is the only one to retain these.

Continued Significance

Even after deadly class riots had disturbed the tranquility on Astor Place on May 10th, 1849, public interest in La Grange Terrace persisted. Although some units had been converted to boarding houses and hotels, the “New York Daguerreotyped” series in Putnam’s Magazine of 1854 affirmed continuing significance. The author criticized some features, but the old-fashioned La Grange was appreciated, despite being unlike the stylish Italianate mansions that were in fashion. The 1845 John Cox Stevens “palace,” built west of City Hall by Alexander Jackson Davis, was also illustrated, and showed the sustainability of Grecian architecture in a perfected Hellenistic mode.

In the 1850s, institutions joined hotels and boarding houses at La Grange Terrace. Columbia College’s Law School moved into a central unit in 1857. Toward the end of the 19th century, some units were remodeled into offices. The northernmost house was the first to lose the iron railings, gradual steps and the candelabra of its “handsome court.” An Episcopalian journal, The Churchman, was edited, printed and distributed from the altered building. Having broken through the front walls, dollies had direct access to the basement. A two-story penthouse was also added to expand office space. Around 1890, the owners of the Colonnade Hotel retooled the “handsome courts” to update the entries for public ease.

A drastic change occurred in 1900 when New York City opened the quiet Lafayette Place southward to City Hall. For 75 years it had begun at Great Jones Street, crossed Fourth and terminated at Astor Place. Now the linked chains of streets became a thoroughfare – Lafayette Street.Newspapers chronicled successive encroachments on La Grange as the incremental widening of Lafayette through 1920 took out all vestiges of cast-iron enclosures and marble entries. Excavation for the Lexington Avenue subway coincided with the opening of Lafayette. Meanwhile, light-manufacturing companies tore out most trabeation and the portals for easier access by dollies to the street level, and created steep descents into basement workshops. In comparison to the sack of 1902, the removal of elements was of slight importance. Wanamaker’s Department Store demolished the five southern structures to erect a warehouse just south of their Astor Place location. In the horror of losing a majority of the row, someone hired Wurts Brothers, architectural photographers, to take five invaluable photographs. Two showed the detail of the entry trabeation and its adjacent bay. Another documented, Diane Arbus style, the newly exposed section of the buildings following the demolition of the fifth unit. In compensation, the two southern survivors were remodeled around 1918 into “bachelors’ apartments.”

La Grange Terrace was rarely highlighted during the second quarter of the 20th century. Probably because the brick row on Washington Square remained patrician, the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) measured one house there in 1937. During the Depression, the area east of Broadway was a slum. The HABS made no effort to disentangle the warren of jerry-built apartments that subdivided the once generous drawing, dining and bedrooms at La Grange Terrace. Since the 1910s, back garden plots were also congested with factory buildings. Only one unit retains an open area, with the original brick wall exposed to view.

La Grange Terrace was one of the first buildings designated a landmark by the New York Preservation Ordinance. The four marble façades are co-owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and property owners.

Beyond Restoration

What is left of La Grange Terrace is irrevocably injured. Architects before me have loved and been influenced by the buildings. Like them, I have measured, drawn and photographed the remains to attempt a graphic restitution and to promote the buildings’ seminal importance in what was a vital phase of cultural expression in the U.S. during the 1830s.

These buildings will not be restored physically. Although aspiring billionaires live in a sinuous but wooden Astor Place up the street and the Blue Man Group attracts families from around the world to the old Astor Theatre, no one wants to revive the palatial drawing rooms upstairs. The antiquarian ideals of Colonial Revival connoisseurship are dead.

To physically restore La Grange Terrace would entail emulating the Japanese appreciation for their 19th-century past at Meiji-Mura. The existing structures would be disassembled and moved to an outdoor location, such as the Metropolitan Museum. Curators mused about this scenario during the 1960s. Building components that the astute Hewitt sisters saved around 1915 would have to be repatriated from Ringwood State Park. Elements known only through historical photographs would be replicated. Cast-iron rails that enclosed the “handsome courts” and the regal marble portals that imitated an Athenian monument to poetic victory would need to be rebuilt. Although walking around such a restoration would be delightful, it will not happen. We must enjoy the shadow of the original structure while we create a virtual tour. Too much is lost, and not only from demolition.

A New York Style

La Grange Terrace was the crucible within which Alexander Jackson Davis, James H. Dakin, and perhaps others, developed a New York Style of Grecian architecture. They continued to refine this vision in town and along the Hudson River in residential and civic buildings. Davis designed numerous rows of elegant terraces, generally more severe than those on Lafayette Place. In 1834, he sent drawings to Owego, NY, for a substantial La Grange-type wooden residence that exists in mint condition.

Although it remains unclear exactly what the impetus was for its design and execution, La Grange Terrace is an extraordinary structure that achieved a distinctly American, and further, New York, expression. La Grange Terrace embodied the aspiration to develop a metropolitan style of Grecian architecture, and this was projected nationwide through books, the outward journeys of architects, and eventually the distribution of manufactured products of architectural embellishment.

Mid-decade, the inventive James H. Dakin took his drawings and experience to Mobile and New Orleans, and literally rebuilt the New York approach in those thriving cities. Likewise, the more opaque figure Charles F. Reichardt transported the New York view to Charleston in the service of the Hamptons. For Wade Hampton II, he built the Charleston Hotel, and for his half sister, Susan Hampton Manning, he built Milford in the country. Susan and her husband, John Laurence Manning, filled the great house with Grecian furniture by New York’s Duncan Phyfe. Finally, Minard Lafever, best known for his architectural books that disseminated the New York Style, built the First Presbyterian (Mariner’s) Church in Sag Harbor, NY, and probably sent plans with similar details to build a wooden Ionic house for a hard working and successful yeoman farmer near Vermillion, OH.

Even further abroad, in 1844 the builder Francis Costigan constructed a grand house for J.F.D. Lanier above the banks of the Ohio River in Madison, IN. The architectural elements derive from Lafever’s Beauties of Modern Architecture, and thus from the nucleus of the New York culture founded in and around La Grange Terrace.