Restoration & Renovation

Restoring Frank Lloyd Wright’s Darwin D. Martin House

Frank Lloyd Wright, arguably the most influential architect of the 20th century, is distinguished for the genius ways in which he wed the built environment with its natural environs. The Darwin D. Martin House (1903–1905) is a prime example of that genius. In fact, the 1.5-acre property is considered one of Wright’s crowning Prairie-style achievements. The National Historic Landmark is located in the Parkside Historic District of Buffalo, New York, and was commissioned by 37-year-old Martin, a self-made billionaire and secretary of the Larkin Soap Company. Martin and his wife, Isabelle, lived in the home from 1905 to 1937, after which time it remained vacant for 17 years.

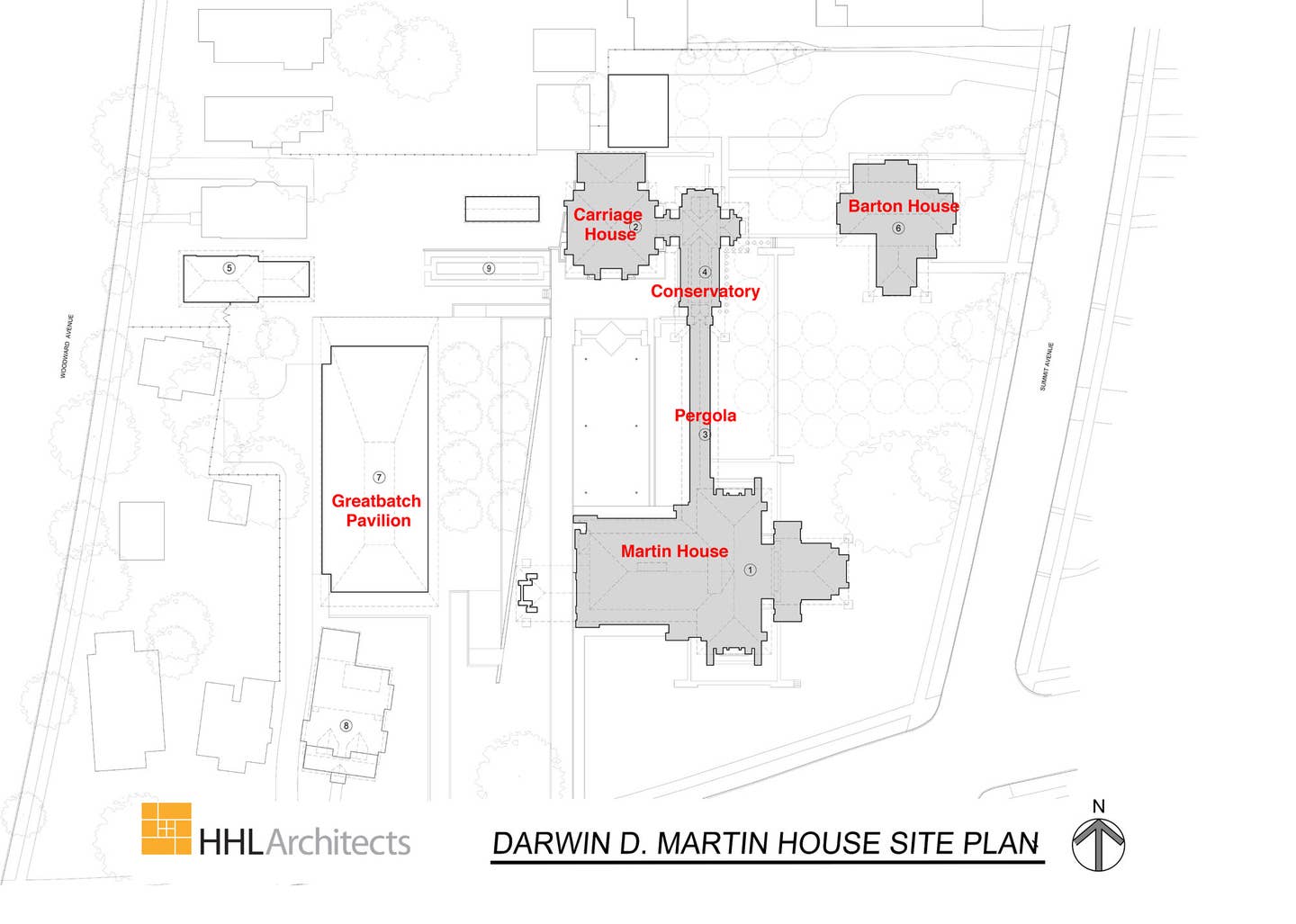

After decades of neglect and subsequent states of ownership resulting in partial demolition, the property found its savior. In 1992, the Martin House Restoration Corporation (MHRC) began raising the necessary funds to oversee the property’s complete restoration. Major work began in 1997, and in 2009, the Eleanor and Wilson Greatbatch Pavilion was opened to the public as a visitor center. The $50 billion project goal is to restore the entire property to its 1907 state for use as a public museum.

Darwin D. Martin House

The residential complex comprises six interconnected buildings: the Martin House, the George Barton House—where Martin’s sister and brother-in-law once lived—a carriage house, a conservatory, the pavilion, and a gardener’s cottage, which was added in 1908. Other significant structures include a pergola connecting the Martin House to the conservatory, and a greenhouse.

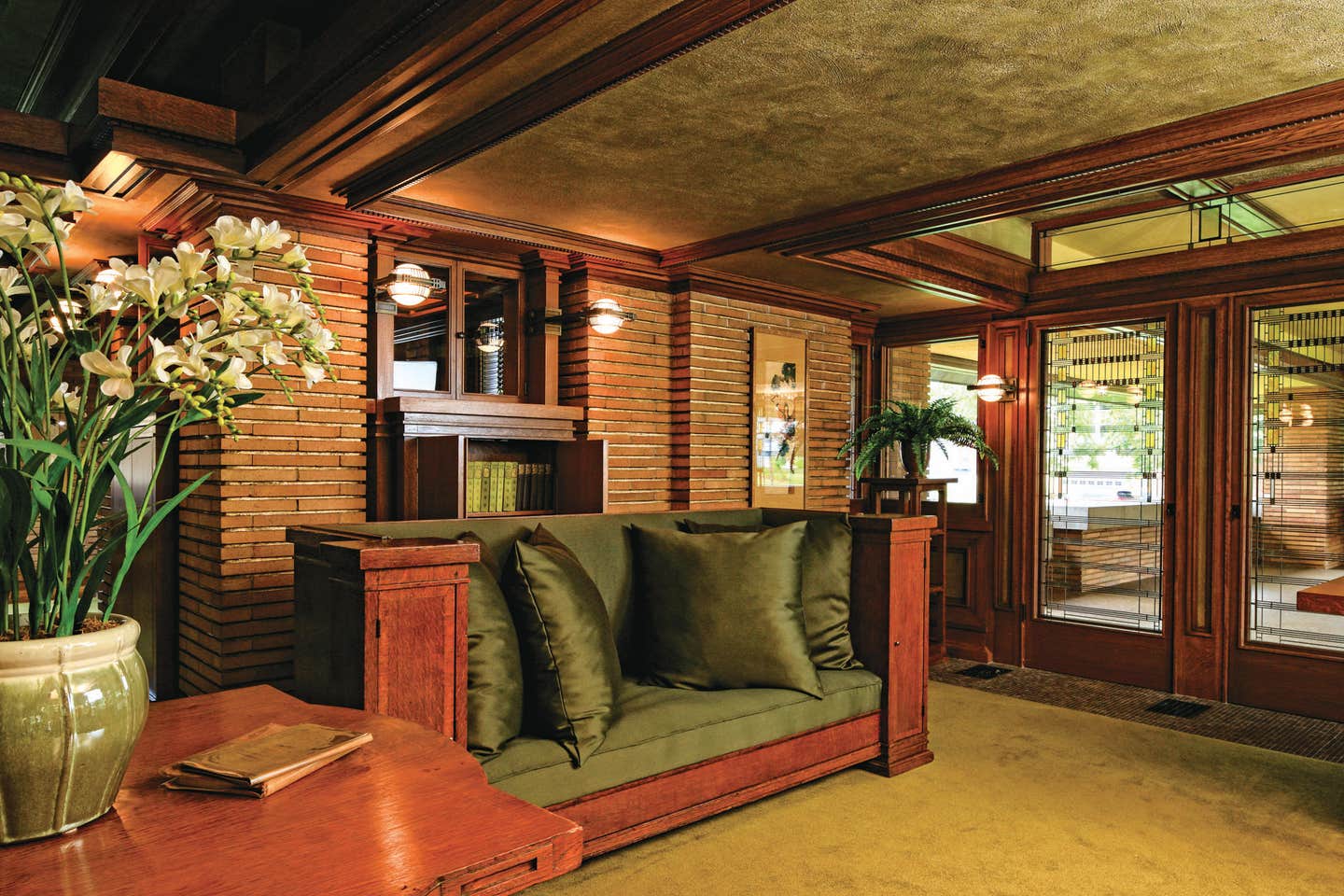

The Martin House demonstrates the strong horizontal planes, deep overhangs, cantilevered roof, grounded foundation, and central hearth for which Wright was famed. To date, its exterior reconstruction and renovations are complete. The next phase, now underway, is focused on the interiors. (It is significant to note that no other Wright site has undergone such degradation and remained standing.)

The home’s pièce de résistance is the wisteria mosaic fireplace. Though fireplaces feature prominently in Wright’s residential designs, few included a mosaic element. The 360-degree glass work spans all four walls of the double-sided fireplace, which provides a spatial divide between the entry and main living area. Wright’s beloved bronze, gold, and green palette colors the patterns of winding wisteria vines—a natural element found in the exterior landscape. Most of the original mosaic was lost to damage that occurred during the 17-year vacancy, though salvaged tiles were incorporated into the replicated mosaic. The restoration took two years to complete, and was the purview of Botti Studio of Architectural Arts—a family-operated business with roots that date back to the 16th century—in collaboration with HHL Architects.

Spearheaded by founding Architect, Theodore Lownie, HHL Architects initially joined the project in the early 1990s, when the University of Buffalo owned the property. The firm was called in to assist with the reparation of a second-floor glass porch, which evolved into a project to restore the roof on the 50,000-square-foot Martin House. “It’s almost a hybrid between a commercial building with concrete and steel components, and a lot of [more residential] wood framing,” notes Matthew Meier, AIA. Replicating building materials, which during Wright’s time would have been fairly conventional and easily found, proved challenging. For the terra cotta roof shingles, for example, they used a 300-year-old company based in France that makes shingles by hand. “We couldn’t re-create them using the original manufacturer because they don’t make them that way anymore,” Meier explains.

Project manager Jamie Robideau describes the impact the materials had on construction: “There’s a learning curve . . . [today’s] workforce hasn’t worked with this type of terra cotta tile or plaster or style of masonry. They had to use special mortars and rake the joints in the manner needed for this project. Our masons, roofers, plasterers, and woodworkers all had to get acquainted with older methods or create new methods to mimic what [the original builders] were able to achieve.”

The house includes 394 works of glass art designed by Wright—more than any of his other projects.

Art glass pieces, which Wright referred to as “light screens,” were vital to his Prairie style. They feature in windows, doors, skylights, and laylights or “false” skylights that run horizontally and are electrically illuminated. This project is home to the “Tree of Life” windows—Wright’s most famous glass work. Alone, it contains 750 individual panes of glass. The design intent was to connect the inside experience to the natural world beyond; Wright used casement windows because they literally open into the landscape, and invite it in.

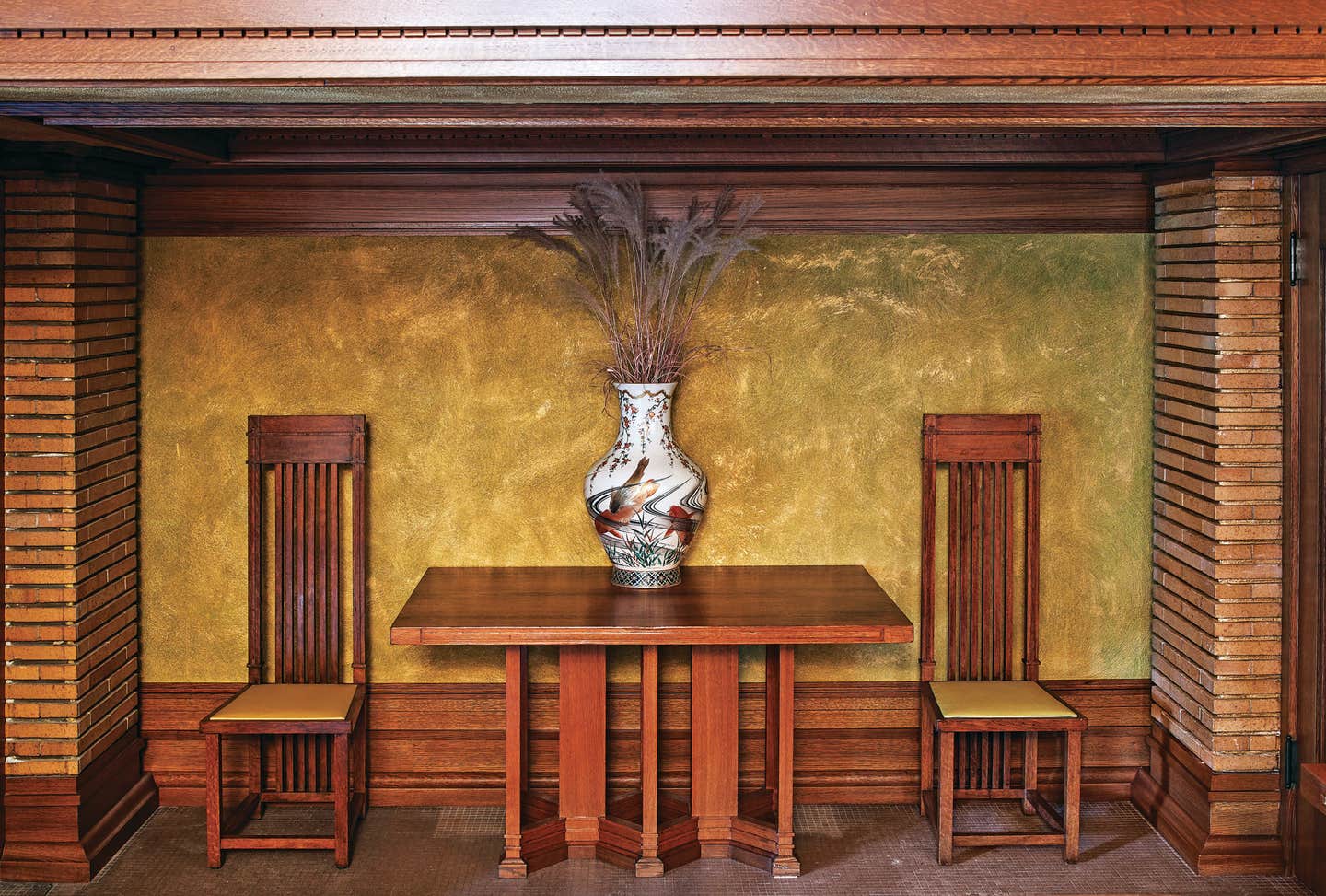

“It’s a complicated facility,” says Meier. “Everything about the architecture and the finishes was integrated—the trim was part of the structure, and the exposed brick within the house was also part of the structure. Back then, that was a foreign [idea].” He cites the multiple built-in elements—some of which housed radiators, others books, chinaware, and kitchen cabinetry. “This was really his first signature Prairie house that integrated everything—the walls, the ceilings, the inside and outside, the furnishings. The dining room table was built no differently than the wall trim.”

Wright designed all of the furniture and selected the artwork—the team worked to both restore the pieces still on hand and to re-create all of the missing components including fabrics, color washes, and finishes, which Meier describes as an “almost archeological” process.

As the landscape is integral to all Frank Lloyd Wright designs, MHRC is currently planning for the rehabilitation of the property’s historic grounds and gardens. The strategy for the preservation and management of the landscape is based on a recently published planning document, called the Cultural Landscape Report (CLR), which was produced by Bayer Landscape Architecture, PLLC, in consultation with MHRC and HHL Architects. “The CLR establishes the Martin House landscape as an important contributing attribute to the overall significance of the historic property,” says MHRC Executive Director Mary F. Roberts. “An accurately documented and rehabilitated landscape is vitally important and lies at the heart of the historic restoration of one of New York State’s most prominent architectural icons.”