Restoration & Renovation

A Study in Preservation: Tuthill’s Townhouse Gets a 21st-Century Update

After reconfiguring the garden-

level floor plan, and installing

new glass-and-steel patio

doors, the dining room is now

filled with natural light.

When William Burnet Tuthill was commissioned to design Carnegie Hall in 1889, many people were bewildered. But Tuthill, an architect and cellist who had never designed a concert venue, surprised them with an elegantly styled and beautifully resonant performance space.

While he is best known for Carnegie Hall, over his career Tuthill designed many notable buildings in New York City and elsewhere. Among them is a row of three identical townhouses in the West Village. Built in 1888, near the close of the Gilded Age, the buildings sit across from two other Tuthill-designed townhouses in a leafy neighborhood that evokes settings from novels by Henry James and Edith Wharton.

One of the trio of townhouses was recently bought by a new owner whose enthusiasm for the historical aspects of the home wasn’t dampened by a late-1980s renovation that had stripped away much of its character. To bring back those details as well as make necessary structural improvements, a team was assembled that included Shadow Architects, Ward + Gray, and contractor Green Conversions, Inc.

The exterior of the three-story, 3,000-square-foot townhouse, which Tuthill had designed as a blend of Romanesque Revival and Queen Anne elements, was in good shape. “We had to do very little on the front facade,” says Larry Cohn, principal at Shadow Architects, indicating the building’s decorative red brickwork, overscaled wood entry doors, iron railings, and arched windows at the second-floor level.

But behind the near perfection of the preserved facade, much of the home’s original charm had been erased. “This project was meant to bring back the glory of the original house,” says Cohn.

While Shadow addressed structural and waterproofing issues, coordinating new mechanicals, electric, and plumbing—often concealing them in ways that didn’t detract from the period aesthetic—Ward + Gray turned its attention to the interiors. Fortuitously, the principals, Christie Ward and Staver Gray, came across a book, The City Residence: Its Design and Construction, written by Tuthill and published in 1890. The thorough, 200-page guide became a significant source of inspiration for both the interior designers and the architect.

“After we dove into Tuthill’s work, we knew we wanted to keep the shell of the townhouse as traditional and as historically accurate as we could,” says Ward, noting that Shadow was aligned with this approach. Also taken into consideration was the lifestyle of the townhouse’s new occupants, a young couple. “It was important to make it feel relevant to them and not entirely serious,” says Ward, with Gray adding that “we tried to create tension with the furniture, more modern and collected,” against the Gilded Age backdrop.

Right, Taking cues from Tuthill’s published pattern book, the main parlor living room now has new wainscot around the perimeter and restored crown moldings.

The floor plans were modified for the kitchen and dining area on the garden level and for the primary suite on the third floor. Except for the garden level, which was gutted, renovating the rest of the townhouse first required determining what was worth saving and then successfully blending old and new. “We had to figure out which features to keep in place, to preserve, and then we had to decide whether to update because we wanted to make changes or because something was falling apart,” explains Cohn. For example, of the five original fireplaces, three were restored, and two were remodeled, one using an 18th-century surround shipped from Italy in pieces. The parlor level staircase was repainted, its railings stripped and ebonized. The floors are original and refinished.

salvaged and reinstalled, with new trim.

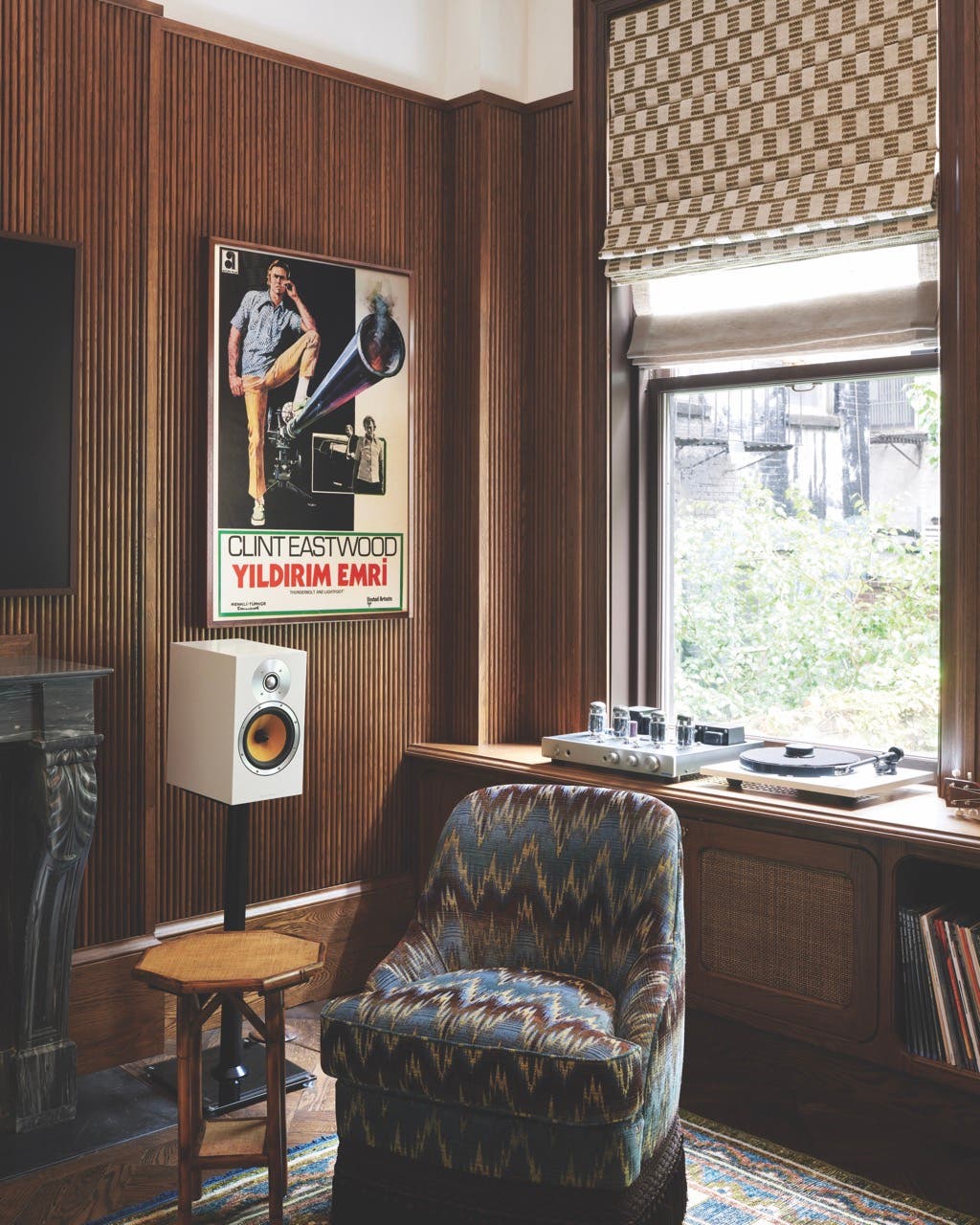

Reeded wood paneling, ample built-in storage, and a vintage fireplace

surround elevate the den, once stripped down to its original brickwork.

Original crown moldings in the living room were restored while new wainscot based on a pattern found in Tuthill’s book was added around the perimeter and down the stairs to the kitchen. Reeded oak paneling in the den, also inspired by a Tuthill-designed pattern, introduces a midcentury modern look to the cozy room where the owners read and listen to music. “The idea is that it’s an updated library,” says Ward, explaining that inspiration for the shelving derived from an 1800s Tuthill-designed pharmacy.

In the kitchen, the focus is on the prominent Lacanche cooking

range and marble countertops, range hood, and backsplash.

For the primary suite, a previously choppy layout was reworked so that there is a continuous flow, with a hallway from the bedroom flanked by a pair of closets leading to the primary bath. Ivory-toned paint on restored and new plaster walls makes the space feel serene and calm. The custom marble patterned floor tile in the primary bath is a nod to the couple’s engagement in Rome, which took place while their townhouse was being worked on. “We found this tile from a church in Rome and recreated it for the bathroom to have a personal element,” says Ward. In a corridor seating area, Ward + Gray designed an ebonized oak piece that serves as a coffee station, so the couple can get ready in the morning and not have to walk downstairs to the kitchen.

storage. In the primary bathroom, custom floor tiles were inspired by a floor

the interior designers saw in a Roman church.

Throughout the house, even in the more contemporary-leaning kitchen and primary suite, the designers strived to incorporate elements that reference the past. Sometimes this was accomplished by cleverly retrofitting vintage pieces they found at auction, like a cabinet turned into a wet bar in the library, an armoire in the dining room modified to conceal a wine refrigerator, and a storage piece for towels in the primary bath that’s an 1820s Irish bookshelf.

The new kitchen with marble countertops and a Lacanche range has traditional millwork paneling that conceals appliances and tall storage. “When we saw the state of the kitchen, it was devoid of any architectural detail, so bringing back those classical elements was helpful,” says Ward. The original wood shutters were removed, restored, and replaced in their original location, with new trim. Gray says they painted the now open-plan space in ivory to help reflect light, and to brighten up the garden level further, Ketra smart lighting was installed, which automatically adjusts the light color to reflect the time of day.

eye touches in the primary bedroom on the top floor of the townhouse.

Middle and right, in the guest bedroom, the clients’ own art complements

custom fabrics by Pierre Frey, on the bed, and George Spencer Designs,

on the bench. Seated at the desk, one overlooks the leafy back patio.

On the outer wall of the dining room the architects coordinated new metal-and-glass French doors that open to the garden patio, where new drainage was installed to address past water infiltration issues. The space where in Tuthill’s day laundry was hung out to dry is now a charming outdoor seating area bracketed on one side by a wall of ivy. O

In Tuthill’s introduction to The City Residence, he writes, “To well plan a city residence is by no means an easy task.” Today, more than a century later, the team who restored this West Village treasure, and its owner, would certainly agree—adding, presumably, that the rewards exceed the effort. TB